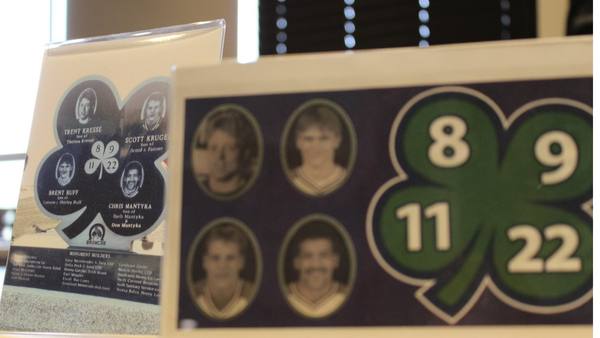

On a frigid afternoon on December 30, 1986, a bus carrying the Swift Current Broncos, then a Western Hockey League junior team, left downtown Swift Current bound for Regina. Four kilometres down the highway, the bus skidded on black ice, slipped into a ditch and flipped. In an instant, four young players — Trent Kresse, Scott Kruger, Chris Mantyka and Brent Ruff — were killed.

Four decades later, the tragedy remains largely unknown in this country. Especially among younger Canadians and hockey fans who might only know of the equally tragic 2018 Humboldt Broncos bus crash. But for those who lived it, the players, their families, their billets and the small Saskatchewan community of Swift Current, it changed everything.

Today, a 40 year old story is being told anew through Sideways: a 2025 documentary produced by Calgary filmmaker Shayne Putzlocher. It follows the personal journey of bus crash survivor Bob Wilkie. Wilkie went on to play in the NHL with the Detroit Red Wings and Philadelphia Flyers in the early 1990s. But as Sideways reveals, the crash and the silence that followed haunted Wilkie and his teammates for decades.

“It affected us all in so many different ways that it ruined relationships. It blurred futures. It took a lot of people into a dark place that some never recovered, unfortunately, because we didn’t know how to do that,” Wilkie told CBC News in late 2025.

A tragedy without a playbook

Wilkie was 17 years old at the time of the crash. Like many young hockey players he was living far from home, billeted in Swift Current and chasing the dream of being drafted to the NHL. He recalls the surreal speed at which life moved in the aftermath of the bus crash.

“We were playing 10 days later so it was a really quick turnaround from this awful incident to ‘okay, it’s time to get back at it.’ And a lot of us were trying to get drafted that year,” said Wilkie in an interview. There was plenty of shock, grief and tears. But he said there were no formal supports: no sports psychologists, no trauma specialists and no crisis interventions.

At the time, the Broncos were coached by Graham James, the now-disgraced hockey coach later convicted of sexually assaulting players in the 1980s and 1990s. The documentary reveals that after the crash James insisted the team didn’t need counselling.

In Wilkie’s mind, the lack of mental health supports reflected an era when therapy was stigmatized and emotional expression among boys was frowned upon. This went alongside the even darker reality surrounding James’ motivation to cover up his own criminal acts.

“In the 1980s, going to see a psychologist meant you were crazy,” said Wilkie. “But [James] was hiding this secret of molesting members of our team. When you’re a predator, the last thing you’re going to do is allow any outside influence.” And so, the players soldiered on, united in grief but isolated in pain.

The long shadow

During that grim winter and into the years that followed, Wilkie and his teammates were caught between expectation and devastation. They were told to be resilient before anyone ever explained to them what resilience really meant.

Some turned to alcohol. Others shut down emotionally. For Wilkie, the trauma followed him through junior hockey into professional ranks. “I was playing in the NHL and I just couldn’t get rid of these feelings,” he said. “The drinking was completely out of control and that’s where the suicidal ideation started.”

Being alone was unbearable for Wilkie. Sleep brought nightmares and panic attacks emerged every time he boarded a bus in bad weather. And like with so many men (especially athletes raised to be stoic) he struggled to articulate what was happening inside his head.

“Those around me could see this change in my behaviour, but they didn’t know how to start the conversation with me,” Wilkie said. The players shared an unspoken truth. The crash had turned boys into men overnight, but left them emotionally stranded for decades.

Why we didn’t hear about it

Despite its magnitude, the Swift Current bus crash didn’t become a part of Canadian hockey lore. Shayne Putzlocher believes that’s because the sexual abuse scandal that later engulfed coach Graham James overshadowed everything else.

“Everybody only talks about the Graham James stuff and nobody talks about what this community actually went through,” said Putzlocher who has produced over 40 films and 200 TV episodes. The veteran film producer points out there were 20 other people on that bus, yet for years distribution companies, federal funders and broadcasters rejected Putzlocher’s attempts to make a feature film out of it.

“I got turned away everywhere…they didn’t think it was relevant or that there was a big enough audience for it,” he recalled in an interview. Only after repeated setbacks did Putzlocher pivot to a documentary format – his first ever as a film producer. Even then, he only did it because he felt the story needed to be told regardless of profitability.

Watch Sideways with CMHF

We’re proud to be a partner on this film and help bring this story to more Canadians.

Use the promo code CMHFSIDEWAYS to get $5 off the digital download and watch it at home.

A documentary about mental health, not just hockey

When Putzlocher approached Wilkie in 2021about becoming the emotional centrepiece of the film, Wilkie initially hesitated. “I don’t know if I want to put myself out there in the world,” he told Putzlocher. But Wilkie also knew what a documentary could do for men and boys in a positive way and eventually agreed.

What emerged after four years of tireless work isn’t just a hockey documentary; it’s also a mental health film rooted in masculinity and silence. It chronicles Wilkie and fellow survivor Peter Soberlak processing the death of teammate Chris Mantyka on the bus. It also follows Wilkie through the NHL, through the depths of depression, addiction, fatherhood and eventually into wellness coaching through an organization he founded in 2008, I Got Mind.

Sideways also bridges past and present by connecting survivors from the 1986 Swift Current bus crash to survivors and families of the Humboldt crash in 2018. The film highlights how the 1986 survivors used their own long-term experiences with trauma and lack of mental health supports to assist the Humboldt community in a moment of need. And it’s a moment Wilkie describes as crucial for his own healing. “It taught me how resilient we can be.”

The cost of silence and the power of conversation

For Putzlocher, the most powerful reaction has come from audiences who have seen Sideways on tour. “It opens your mind to feel comfortable starting the conversation before it’s too late,” he said, recounting the story of a parent who spoke publicly about their child’s suicide after a screening.

That, he believes, is the point. Young men in Canada are disproportionately affected by suicide and mental health challenges. According to the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention, men are three times more likely to die by suicide, yet less likely to seek help.

Wilkie knows this firsthand: what saved his life wasn’t a miracle, but human connection. Meeting someone he loved, becoming a father and slowly beginning to talk. “Love started to happen and that really opened things up,” he said. But healing didn’t happen overnight; it took Wilkie more than 20 years to begin making peace with what happened on that highway.

A message for men — especially young ones

For boys and men who watch the documentary, Wilkie hopes the message is clear: you are not weak for struggling and you are not broken for needing help.

“When someone can get serious about healing and overcoming, it has a significant impact on all those people around them too,” Wilkie said. Putzlocher puts it more bluntly. “It’s not what’s wrong with them – it’s what happened to them.”

For the boys of Swift Current, what happened on that ill-fated day in 1986 was unthinkable. But through Sideways, Wilkie and Putzlocher are ensuring that what followed – the silence, depression, drinking, suicidal thoughts and the resilience and healing – is finally spoken aloud.

For countless Canadian men and boys facing silent battles of their own, that conversation could be life-changing and-life saving too.

If you or someone you know is thinking about suicide, call or text 9-8-8: Canada’s Suicide Crisis Helpline. Support is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

To learn more about the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention (CASP), its programming and advocacy, visit CASP’s website.

Feeling off?

Start here.

Free tools to help you deal with stress, anxiety, and tough stretches.